Augenblick

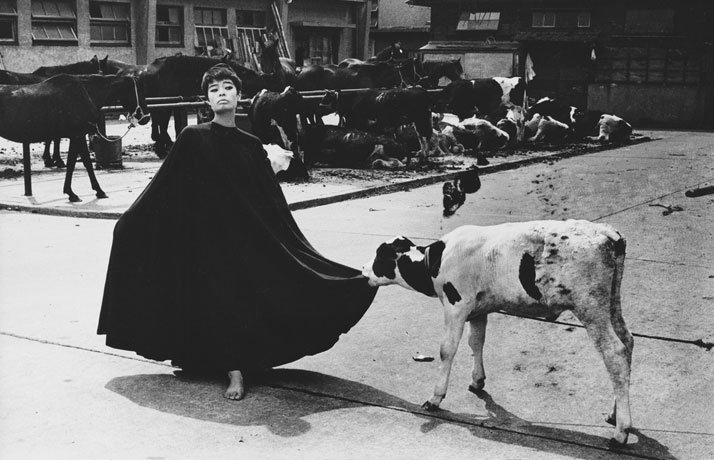

Yoko Wanibe, photographed by Masahisa Fukase in a slaughterhouse near Tokyo Port

“You can’t say you’re a photographer because you take photographs. You can’t say you’re alive just because you live.” Masahisa Fukase produced some extremely despondent photography, morose and shadowy even when the subject matter seems playful, and a statement like this one (found in his papers after his death) really only formalises an idea expressed much more forcefully by his images. Are you alive? Are you really producing art, or has art production become routine? Are you looking without seeing?

It’s easy to take absent-minded photographs. A camera makes mimesis mechanical and automatic. The human operator has to struggle against the technical apparatus to restore a volitional element to the photographic image. This tension between camera and photographer is related to a larger dilemma. Life is full of different determinisms — economic, technological, genetic — and even when we think we’ve escaped them they keep reasserting themselves unexpectedly. Today there are scientists who believe that the mastery of nature is science’s principal end, yet many of these same scientists like to claim that evolutionary logic is an inescapable reality to which we all must submit. Like their counterparts in the economics faculty, they think they know how to distinguish between the things we can change and the things we can only observe. But the impoverished pragmatism of Niebuhr’s ‘Serenity Prayer’ (beloved by North Americans) becomes a con when ‘the wisdom to know the difference’ is foisted on us from above, enshrined in law, exempted from criticism. When we resign ourselves to the ‘things we cannot change’ we transform a political decision into a disinterested observation. The subtlety of dialectical thinking gives way to the self-destructive realism of the OODA loop. Self-preservation isn’t life; empirical observation isn’t sight; and the relationship between the two activities — looking and living — will vary depending on the relative hopelessness of our situation.

Never before has censorship been so perfect. Never before have those who are still led to believe, in a few countries, that they remain free citizens, been less entitled to make their opinions heard, wherever it is a matter of choices affecting their real lives. Never before has it been possible to lie to them so brazenly. The spectator is simply supposed to know nothing, and deserve nothing. Those who are always watching to see what happens next will never act: such must be the spectator’s condition.

—Guy Debord, Comments on the Society of the Spectacle

Aesthetic pleasures are always closely connected to the deliberateness of art and spectatorship. This is true even for the contingent parts of an artwork (a detail may be unintended, but it is always a side-effect of the original design). Very few aesthetic experiences escape this rule. An atheist looking at a sunset imagines he is impressed by dispassionate, huge, non-volitional physical processes, but on a more fundamental level he enjoys his own apprehension of the scene. There’s always a bit of mastery, control, and discernment involved in the act of looking. But the ultramodern world is now succumbing to tendencies that are a hundred times removed from anything like an interpretable ‘intention’. The iron laws of mechanised economic growth have very nearly developed to the point where they are no longer subject to the control of human institutions; the changes in the earth’s atmosphere, oceans, and ecosystems may have already turned exponential and irreversible. Not only have these tendencies escaped human control, they are also increasingly resistant to contemplation, even at an extremely abstract level. Their effects will eventually destroy art’s conditions of possibility. In the meantime they cannot even be ‘looked at’.

Anagnorisis: There are many of us, but we’re not always easy to spot. We live like we’re anticipating something. Depression is a condition that overtakes you after a disturbing realisation. The particular content of this realisation doesn’t matter. It only has to make your bad circumstances seem endless. You begin to fixate on the unlikelihood of real, positive change. Weirdly enough, the conviction that things are permanently broken causes you to live with one eye on the future. You keep yourself in reserve; your metabolism slows down; you wait for an impossible upheaval, world revolution. You are obsessed with your terrible prospects, and this makes it hard to enjoy anything, but at the same time, in another part of your brain, your refusal to accept this intolerable situation turns into a principled resistance to the normal patterns of life. Anhedonic waiting is a way of bearing witness to how bad things really are.

Depressed people wait for something that can only materialise if they stop waiting; depression is hope travestied. If the world’s depressed people could only make their unworldly disinterest more complete and uncompromising — if they could force themselves to stop waiting and watching — then they would act, happily, in unison, and in a truly deliberate way. They wouldn’t do it for the sake of art, or to preserve a life approximating the alienated form of an artwork. They would act in pursuit of a lived life, a generous immediacy, hoping to discover new forms of excitement and boredom that don’t relentlessly cancel one another; that don’t sting. Every temporal debt would be written off.

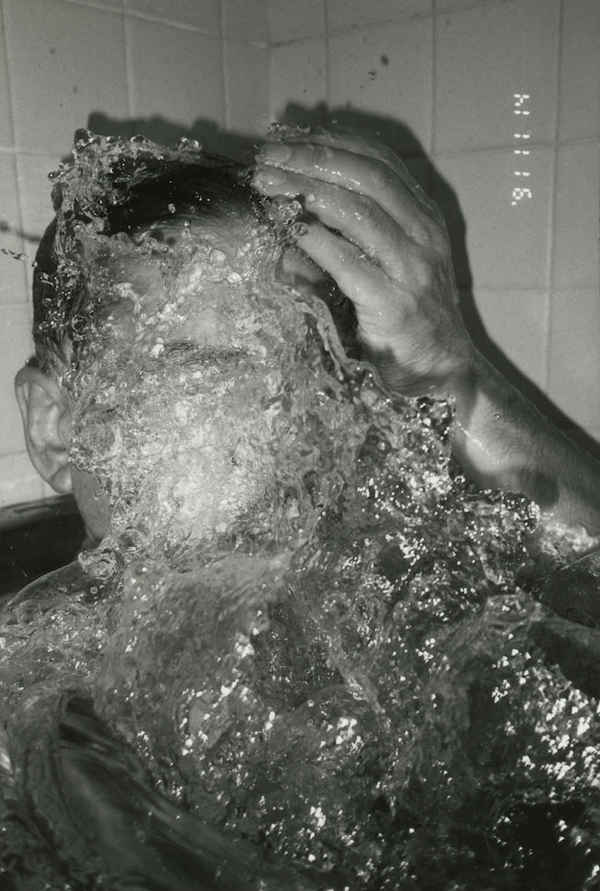

Looking at Fukase’s pictures of his wife, his cats, and (much later) his depressed wallowing in the bath, one starts to suspect that most of us never experience the present. Only the camera captures it — the rest of us are too slow.